Green Ward Competition

Review of the Haemodialysis processes in a single satellite dialysis unit

By: Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

Potential to save 15,828kgCO2e and £33,435.33 per year if changes implemented in all 8 of Leeds dialysis units.

£2,837.05 (Actual)

1,914.4 kgCO2e (Actual)

Team members:

- Jemma Alison Hardy – Satellite Dialysis Unit Sister

- Peter Jones – Renal Technical Services Manager

- Terence Simpson – Renal Technologist

- Dr V R Latha Gullapudi - Consultant Nephrologist

- Dr Mark Wright- Consultant Nephrologist and Haemodialysis Lead

Aims:

- Reducing the number of disinfections of the dialysis machines to once in 24 hrs in staggered manner and replacing the others with rinsing process

- Once the initial priming process of the dialysis machines is complete, placing them standby mode whilst waiting to connect patients to the machine

- Reducing the number of pharmacy deliveries from weekly to biweekly to the satellite dialysis unit

Background:

Haemodialysis is lifesaving therapy for patients with kidney failure. However, it comes with huge environmental costs as it involves usage of vast amount of medical consumables, water, and electricity. It is estimated that 3.8 tonnes of carbon-dioxide equivalent emissions are produced by one patient’s dialysis treatment per year (1). In the unit under review, we provide services to our patients in two different shifts per day. This means that a single dialysis machine is routinely used for provision of two dialysis treatments in a 24 hour period. Dialysis machines are primed and turned on at the beginning of the day, meaning dialysis fluid runs continuously whilst waiting for the patients to be connected. Each dialysis machine gets three heat disinfections per day.

Methods:

We started by creating a process map of the steps from the production of dialysis fluid to use of dialysis machine to identify our aims as above. We discussed aims 1 and 2 with the other staff members on the unit during the daily handovers. The majority of staff were enthusiastic to try the suggested changes which supported embedding these changes into everyday routines. A similar approach was adopted for Aim 3 by seeking staff opinions, exploring the availability of storage space, rearranging storage cupboards to improve utilisation of the available space, and relabelling of the cupboards as per the new agreed storage arrangements.

Measurement:

Baseline data was collected on

- Aim 1: electricity and water usage with each episode of disinfection and rinse during 24 hour periods for one dialysis machine. We then projected the electricity and water use over one year.

- Aim 2: the average waiting times between the dialysis machined being primed and turned on, to when a patient was connected. We then measured the consumption of electricity, water and central acid usage during this waiting time per minute and projected it over a: one-year period. There is a scope for further savings from this change by reduced number of central acid deliveries, however it is not possible to precisely calculate at this stage.

- Aim 3: Reducing pharmacy deliveries from weekly to biweekly will lead to an average saving of 104 miles in transportation per year. We are liaising with the teams at the other satellite units within the Trust to investigate if the same change is feasible in their setting. This would yield higher milage savings.

Results:

In total, changes implemented will save 1,914.4 kgCO2e and £2,837.05.

- electricity: 1,672.3kgCO2e and £1,285.90

- water: 41.8kgCO2e and £264.90

- travel (miles): 9.8kgCO2e and £58.24

- acid savings: 190.3kgCO2e and £1,228.00

This satellite unit is a part of Leeds Haemodialysis services which currently provides care provision for 550 incentre dialysis patients in 8 different dialysis units. After taking into consideration of the shift patterns in each unit, if we implement aims 1 and 2 across our haemodialysis services, the estimated savings will be much higher, with 15,828kgCO2e and £33,435.33 saved per year.

If the same small changes were possible for all 24,365 people receiving dialysis in the UK2 and energy consumption of all dialysis equipment was similar across the 70 renal centres in the UK, the national reduction in CO2 emissions could be in the region of 4,495kg per treatment session. If everyone was having dialysis thrice per week, that would reduce CO2 emissions by approximately 700 tonnes per year. Social sustainability and clinical outcomes: The proposed changes may not directly impact individual patient experience but may contribute to an improvement in the turnaround of the patients in the dialysis unit, for example from saving time by replacement of disinfection (40 minutes) with rinse (9 minutes) of the machine in between patients. The unit is planning to move from a 2 shift to 3 shift cycle. Our new system will support in reduce staff workload.

Steps taken to ensure lasting change and conclusion:

We were pleasantly surprised by how much we could reduce our central acid water and electricity consumptions with relatively simple changes. Meeting with colleagues regularly and tackling a different sort of problem to usual was really uplifting and motivating, especially when we realised how much potential benefit there would be when we roll out across the service. Our next steps are to spread this enthusiasm by sharing our project aims and finding at an upcoming departmental meeting, and to explore if the other satellite units would consider a reduction in their pharmacy deliveries.

We are continuing to explore options for additional projects

- Aim 4: Water wastage from the purification process and system was measured as 1,337,000 litres/ year. Across the service equates to approximately 16,848,000 L of water wasted per year (equivalent to 6 Olympic sized swimming pools). We are liaising with appropriate teams to enable redirection of this water to grey water systems of our healthcare setting. Significant progress has been made in one of our other satellite dialysis units and we are looking forward to continuing this work to maximise the benefit of water preservation.

- Aim 5: We use acid supplied in 6 litre plastic canisters and our standard practice is to use one canister for each patient/ treatment. The leftover acid goes down the drain systems. On measurement of the wastage of the acid, the cumulative wastage of acid comes down to 18.75 Litres over 10 dialysis treatments. We are currently exploring the feasibility of avoiding this wastage, by liaising with the infection control team regarding potential safety issues if we were to use a cannister for multiple patients.

- Aim 6: Currently we do not recycle the plastic acid canisters. We are in discussion with the hospital wastage management team regarding recycling potential of these canisters by using existing steri-melt facilities.

References:

- Connor A, Lillywhite R, Cooke MW. The carbon footprints of home and in-center maintenance hemodialysis in the United Kingdom. Hemodial Int. 2011 Jan;15(1):39-51. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2010.00523.x. Epub 2011 Jan 14. PMID: 21231998.

- UK Renal Registry (2021) 23rd Annual Report- data to 31/12/2019, Bristol, UK. Available from renal.org/audit-research/annual-report

Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust - Haemodialysis

Project developed as part of the 2022 Leeds Green Ward Competition. Full impact report available at Green Ward Competition | Centre for Sustainable Healthcare.

The Patient Environment Action Team (PEAT) Support Clinical Areas to be more Sustainable

By: Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

Please see social sustainability section below

£1652.70 (Estimated)

7000kg CO2e (Estimated)

Team Members

- Jemma Robinson - Facilities Operational Manager

- Carl Hyatt - PEAT Technician

- Matthew Robinson - PEAT Technician

- Claire Flanagan - Facilities Operational Manager

- Project Support - Matthew Quinton - Waste Compliance and Sustainability Manager

Project Aims:

- Successfully implement active dry mix recycling (DMR) and battery recycling through staff engagement and behaviour change, reducing the Trusts Carbon Emissions.

- Engage and increase staff awareness on sustainable actions, via a bespoke’ Sustainability’ leaflet

- Identify ways in which the PEAT team can show continuous commitment to sustainability across the Trust as part of the rolling PEAT programme, in support of the Trust Green Plan and net zero ambition.

Background:

The Patient Environment Action Team (PEAT) undertake a range of tasks including complex cleaning, minor routine maintenance works and repair of defected equipment. Visiting over 60 clinical areas annually, we felt they could play an active role in sustainable practice via meaningful engagement with clinical teams. Strategic choice of project: Recycling is highlighted as a key area of focus in the Trusts Green Plan and is one of the most common requests the sustainability team are asked about. Not only is domestic and clinical waste more costly to the Trust than recycling, but incorrect disposal of hazardous waste such as batteries, could result in additional cost in the form of fines issued to the trust due to non-compliance of appropriate waste disposal. Batteries are a hazardous waste and have potentially toxic metals which can leak into landfills and pollute drinking water if managed inappropriately.

Approach:

Studying the system:An audit established that only 4/56 areas were actively using dry mix recycling (DMR). 0/56 areas had access to battery bins. For most areas, batteries were being placed in a Sharp Smart Waste container.

Engagement: We spoke with clinical staff during our audit, and pleasingly, found they were appreciative of the PEAT work and reported access to DMR and battery recycling would be valuable to them. - We also engaged Matthew Quinton, Waste Compliance and Sustainability Manager, who confirmed that the incorrect disposal methods currently used were costly to the Trust. Access to appropriate battery recycling had also recently been identified as an action for the Trust following an external Waste management audit.

Changes implemented:

DMR and battery recycling bins were installed in areas on the PEAT schedule to ensure viability and sustainability of the project long-term. DMR bins were placed in non-patient facing, clinical staff break rooms only for trial. For the duration of the project, to minimise cross-contamination risks, full battery bins were collected by the PEAT team following contact from the ward clerk. However, a longer-term collection plan of adding this to the trust porter system is being considered. Batteries are collected via the Battery Back Scheme operated by WasteCare.

A sustainability leaflet was shared with clinical areas, including useful contact numbers, information on the Leeds GRASP rewards, Carbon Literacy training, and PEAT ‘let us help you’ section. Contact details for the Trust Sustainability team were also left in a sustainability leaflet, should clinical teams wish to request implementation of DMR in clinical areas.

We successfully initiated and installed DMR and battery recycling for trial across 7 clinical areas.

Measurement

Data was collected between the 7/2/2022 and 18/2/2022.

Environmental: Average number and weight of DMR and battery waste in tonnes was used to calculate carbon savings.

Financial: Matthew Quinton, Waste Compliance and Sustainability Manager, provided costs of various wastes streams to the trust. Prior to implementation of DMR, all waste was disposed of via domestic waste at £97.00 per Tonne. As batteries were being disposed of via sharps bins, an assumption was made that batteries were previously disposed of in clinical waste, and therefore incinerated at £925.00 per Tonne. Use of DMR would reduce the cost to £89.00 per Tonne for recycling. Battery collection is free to the Trust.

Social: Informal feedback was gained by engagement with clinical staff.

Results:

Environmental benefit:

- DMR: Waste disposal emissions were reduced by 9.47 kgCO2e for the 7 areas per week (492.89 kgCO2e per year). If applied to the remaining 79 areas (excluding 4 that already had DMR), the projected annual saving is 5562.62 kgCO2e.

- Battery bins: Emissions reduced by 1.25 kgCO2e on average per week, per trial area. Due to the nature of clinical work, there will be significant variation in how quickly areas fill Battery Bins, making it challenging to accurately project data. We have therefore projected the annual potential savings of battery recycling as a percentage of our actual data. Projected at 70%, the potential annual saving across the 7 trial areas would be 318.5 kgCO2e. As a conservative estimate, if we apply battery recycling across the remaining 76 areas in the trust with 30% applicability, an additional 1,482 kg CO2e could be saved across the Trust.

Financial benefit:

- DMR in the 7 trial areas saved the Trust approximately 50p per week, with an annual saving of £26.11. If applied to the other 79.00 areas with no DMR this would be a projected annual saving of £294.71.

- Battery recycling saved £1.15 on average per area per week. Projected at 70%, there is a potential annual saving of £291.20. Projected at a conservative 30% across remaining 76 areas £1,358 could be saved annually across the Trust.

Social sustainability: Engagement with clinical teams showed that staff care about becoming more sustainable. The sustainability leaflet has supported awareness and so far, the sustainability team have received three emails to request DMR recycling in clinical areas. Matron, Honey from Ward J04 said

“The implementation of DMR and Battery recycling has been very beneficial to the area as it is cost effective and good for the environment” and

”The PEAT team are an asset to the Trust, very helpful and always willing to go above and beyond in their works, improving the Patient Environment”.

Steps taken to ensure lasting change and conclusion:

Meaningful engagement between PEAT Technicians and clinical staff has been key to successful implementation of this project. Whilst continued long-term implementation of DMR and Battery bin recycling will transition to the Trust’s Sustainability team, we feel our project has shown that all staff have a role to play in achieving net zero ambitions. We will continue to embed sustainable improvements into our work. A sustainability assurance section has been added to the PEAT ‘works carried out sign off sheet’ including staff engagement actions to promote the aims of this project. Two successful stock room reviews have been carried out jointly with ward clerks with issues including out of date stock, stock no longer required in the area, and ample stock with ongoing continuous orders risking additional out of date items noted. We are continuing to ‘study the system’ and identify change ideas jointly with clinical teams to support streamlining stock ordering and storage management.

Project developed as part of the 2022 Leeds Green Ward Competition. Full impact report available at Green Ward Competition | Centre for Sustainable Healthcare.

Changing the 3 monthly blood test postage kits for patients on the renal transplant register

By: Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

Please see social sustainability and clinical and health outcomes sections below

£1951.38 (Actual)

1219.9 kgCO2e (Actual)

Team members:

- Natalie Bird - Clinical Nurse Specialist, Renal Transplant

- Laura Kirk - Clinical Nurse Specialist, Renal Transplant

- Jo Wales - Clinical Nurse Specialist, Live Renal Donation

- Jo Hitchings - Senior Clinical Support Worker

Project aims:

To measure the environmental, social and financial benefits of a new postal system compared with an old postal system.

Background:

Patients active on the transplant register and those listed for simultaneous kidney and pancreas transplant must have regular blood tests (every 1-3 months) to re-examine their antibodies. With patients all over the region, transporting these samples to the laboratory can be logistically challenging and expensive.

As a team, the renal transplant department is already very proactive in seeking out sustainable changes. Prior to the Green Ward Competition, we implemented changed in the way blood tests are sent to patients. Previously, patients would be sent a blood tube in a “Safe lock” box, which had to be sent back to the hospital from a post office, at an inconvenience to the patient. The boxes themselves were expensive and single use, creating a large amount of plastic waste. Use of a lightweight, recyclable plastic pouch with pre-paid postage labels has been implemented, eliminating the trip to the post office (in favour of the closest post box) to the convenience of patients. As clinical nurse specialists we felt uniquely placed to be able to measure the impact across the triple bottom line of sustainable value and promote implementation of this change on a wider scale.

Approach and measurement:

We audited the number of patients suitable for the change to the new blood test kits. The number of the patients in our clinics changes regularly due to starting dialysis or having a transplant. We estimated on average there will be 11 patients under assessment or active on the simultaneous kidney and pancreas register, requiring monthly blood tests, totalling 132 tests annually. On average there will be 30 low clearance (pre-dialysis) clinic patients active on the transplant register who require 3 monthly blood tests, totalling 90 tests annually. This gave as an average annual total of 222 blood tests completed a year.

Environmental: A process-based carbon foot-printing analysis looking at the extraction of the raw materials and disposal was used to estimate the carbon footprint of both kits (blood tests were the same in both kits and therefore excluded from analysis). Data on the type of material was taken from product specification sheets, and each material weighed. It was assumed both kits were disposed of in domestic waste as despite part of the new kit being recyclable, we cannot rely on staff consistently separating and recycling this section. Financial data was used to estimate the carbon emissions associated with postage. For this analysis we looked only at the emissions associated with sending the kits from the hospital to the patient only.

Financial: Postage cost was provided by the hospital postal room.

Social: We conducted semi-structured telephone interviews with previous patients who have used both kits. We also liaised with the Manchester renal transplant coordinators, as their service continues to use Safe Lock boxes, to inspire larger-scale change.

Results:

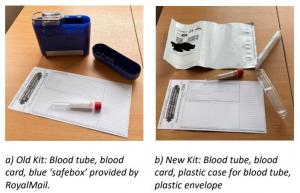

Environmental benefit: The total emissions per test (kit + postage) were reduced by 5.495 kgCO2e, extrapolated across a year with 222 tests sent, this is a saving of 1219.9 kgCO2e. a) Old Kit: Blood tube, blood card, blue ‘safebox’ provided by RoyalMail. b) New Kit: Blood tube, blood card, plastic case for blood tube, plastic envelope

Financial benefit: The old kits cost including postage cost £13.20, whereas the new kits cost £4.41 (3.83 + 58p per plastic container for blood tube). With a saving of £8.79 per kit, we will save £1951.38 per year. With the old kits, we were charged for every kit ordered. With the new kits, we are only charged for blood samples returned, and the envelopes are free, so we won’t be charged for tests that are not completed for patient care.

Social sustainability: Our telephone interviews with patients showed that the new postage kits are easier to use and more convenient to return. Some patients stated they had to pay for the blue lock boxes to be sent a couple of times out of their own money and described them as ‘expensive and seemed unnecessary’. While some patients had no preference for either kit, no negative feedback was received for the new kits.

“I used to use the old lock boxes to send bloods to Manchester. I have to say I really didn’t trust them, they were very bulky but also felt like they wouldn’t close properly so was worried the samples might fall out easily. They weren’t very easy to close.”

“From my house it was 2 miles there 2 miles back so 4 miles in total to post the lock boxes. I also found it quite annoying as I work full time and struggled getting to the post office in time to post them before they closed.”

“I am partially sighted so find it quite fiddly / tricky putting the bloods in here and getting myself to and from the post office.”

For staff, the old lock boxes were described as “fiddly and bulky” so organising and sending out new kits via internal post has been easier and faster for staff in the renal transplant office. Dialysis staff stated they preferred the new smaller postage boxes as the blue boxes were ‘difficult to close properly’.

Clinical and health outcomes: Patient health outcomes have not been negatively impacted by using the new postal kits. Some patients may be able to post their kits more quickly, leading to faster results and care. Some patients have stated rather than driving in a car or using public transport to get their lock boxes to the post office they now walk to their nearest post box instead, which potentially may have indirect benefits of increased physical activity.

Steps taken to ensure lasting change:

Our financial savings have been recognised and celebrated by Paul Jackson, the Abdominal Medicine and Surgery Clinical Service Unit (AMS) project manager for sustainability and transformation and the wider AMS management team. We are also continuing to collaborate with the Manchester renal transplant coordinators. We have shared our data and new postal kit products to support the team in rolling out the same service for their patients. Manchester sends an average of 20 SafeLock blood tests per month. If these 240 tests annually were changed, an additional 1,318.80 kgCO2e and £2,109.60 would be saved. We have regular meetings with other hospitals in the region including Bradford, Hull and York, and plan to present findings here to encourage change to other regional teams. There may be opportunities to share our outcomes further at national network meetings associated with NHS Blood and Transplant or the British Transplant Society to potentially scale our changes to many of the additional 21 transplant centres in the UK.

Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust - Renal Transplant

Project developed as part of the 2022 Leeds Green Ward Competition. Full impact report available at Green Ward Competition | Centre for Sustainable Healthcare.

The Gloves are Off in the Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU)

By: Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

Please see social sustainability and clinical and health outcomes below

£1965.81 - £3216.79 (Estimated)

2242.73 kgCO2e - 3997.19 kgCO2e (Estimated)

Team Members:

- Grace Crossland - PICU Staff Nurse

- Dr Jonathan Ince - Simulation Fellow, LTHT

- Dr Alex Olney - ST3, Paediatrics

Aim: To reduce use of non-indicated sterile gloves during preparation and administration of oral and enteral medications on PICU.

Strategic choice of project: During the pandemic the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) has escalated to an unprecedented level, however there is reasonable evidence to suggest that frequent, untargeted glove use worsens hand hygiene (1) and increasestransmission of preventable infection in our hospital environments (2). The wider PICU team have recently declared their wish to actively work towards sustainability, therefore we felt well placed to collaborate on glove usage. We were also inspired by similar changes achieved by Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH), through their gloves off (3) campaign.

Data collection:

We completed audits of patient drug charts to determine the average number of medication preparation and administration events on average per patient per day. We assumed that one pair of gloves would be used per event. However, as many administrations require a second nurse to check the medication beforehand, a glove use factor of 1.5 was applied to these episodes (as multiple pairs of gloves are commonly worn). From this audit data we extrapolated the percentage of glove use attributable to oral and enteral medicine administration and what we could reasonably expect to reduce.

We collected qualitative data from staff on their views on the project and glove usage. We did not gather data from service users as this was deemed inappropriate in the PICU environment when most patients are too young or unwell to communicate, and parents/caregivers are under considerable stress with their child acutely unwell. We considered collecting data from patients, however decided against this due to most patients being intubated and sedated and/or too young to engage. It was also felt to be inappropriate to speak to parents and/or carers given PICU is an incredibly stressful place for them to be.

Changes implemented:

Our audit and research identified non-sterile gloves are not required with certain medications. This was reviewed and agreed by one of the senior nurses on PICU and infection prevention. We commenced an awareness and education campaign focusing on reducing nurse glove use when administering medications. We completed presentations at staff meetings as well as to available staff during breaks. We also created and published a poster board and placed reminder posters at all glove sites on PICU.

Results:

As our trial phase is currently ongoing, we have used our audit data and data provided from the GOSH campaign to make assumptions on potential impacts. Our audit identified that an average of 93.6 individual gloves are used per patient in a 24-hour period. At the time of our audit, there was an average of 11 patients on PICU, equaling 1029.6 gloves used per day. At maximum capacity of 18 patients, this would increase to 1684.8 gloves used per day. There was an average of 9 drug administrations per patient per day. 85.3% of the time, there was a requirement for the medications to be ‘double checked’. We can assume a reduction of glove use in these instances as the nurse no longer needs to wear gloves for preparation and checks, only for administration.

The GOSH gloves off campaign reduced glove use hospital wide by 38.8%. GOSH removed the requirement for non-sterile gloves to be used for additional reasons to our campaign (e.g. when preparing and administrating intravenous medications). As we are focused on nursing preparation and administration of oral and enteral medications only, we do not expect a reduction of 38.8% at this time. However, based on our audit data and data provided by GOSH, we reasonably expect to reduce Glove use by 25% on PICU. A result ranging from PICU occupancy of 11 patients – 18 patients (full capacity) has been given to account for variability in admission numbers.

Environmental benefit: A 25% reduction would save between 2242.73 kgCO2e - 3997.19 kgCO2e per year. These estimates include the production, transport, and incineration of the gloves.

Financial benefit: Cost of gloves was obtained through hospital procurement data from 2019-2020 (pre-covid data). A reduction in use by 25% will save £1965.81 - £3216.79 per year. These estimates include the purchase and disposal (via incineration) of the gloves. There is an expected increase in the price of PPE following the rise in oil price and so the implementation of this project is also crucial from a cost avoidance perspective.

Social sustainability: When delivering the teaching to staff nurses on the unit we found there were many positive attitudes to the change, here are some examples: “Great idea, I think it would be really good to improve our hand hygiene, I feel I often see people not following the correct hand washing policy” “Really good idea, really good that there is such an environmental saving” Positive attitudes towards the project may lead to enhanced engagement and staff morale when knowing that we are making a positive change for our patients, the environment and the trust. There are also health benefits to staff, as the use of non-sterile gloves is known to increase the rate of workplace related contact dermatitis (4)

Clinical and health outcomes: Research shows that inappropriate use of non-sterile gloves decreases hand hygiene compliance due to staff not removing or changing gloves at key moments, therefore missing hand washing opportunities. We expect to see an improvement in hand hygiene and with this brings potential for reduced hospital acquired infections, reduced length of stay and reduced PICU bed days. We plan to retrospectively collect this data following our trial.

Steps taken to ensure lasting change:

To measure the actual impact of our education campaign, we will undertake repeat audits and further non-structured interviews with staff at 6 weeks and 6 months. We plan to provide further education to nursing staff and investigate the possibility of removing non-sterile gloves when preparing and administering IV medications. Internally, the project has gained the support of business management, pharmacy, and the infection control and prevention team. We have longer term goals to embed education of use of non-sterile gloves into new staff inductions; and in widening the project to include all front-line health care workers across the children’s hospital and trust. We have already had other clinical areas get in touch to state their interest in participation. With time, we aim to achieve a similar reduction in glove use as that seen by GOSH.

References

- P.Loveday, S.Lynam, J.Singleton, J.Wilson, 2013, ‘Clinical glove use: healthcare workers' actions and perceptions ’Journal of Hospital Infection, Vol 86, No. 2, Pg. 110-116

- Ashley Flores, Martha Wrigley, Peter Askew, 2020, ‘Use of non-sterile gloves in the ward environment: an evaluation of healthcare workers ’perception of risk and decision making ’Journal of Infection Prevention, Vol. 21, No. 3, Pg. 108-114

- Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) The Gloves are Off campaign: Glove crackdown saves trust £90k and reduces waste | Nursing Times 4. Upton. 2021. https://www.rcn.org.uk/news-and-events/blogs/dermatitis-and-glove-use-make-one-change

Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust - Paediatric Intensive Care Unit

Project developed as part of the 2022 Leeds Green Ward Competition. Full impact report available at Green Ward Competition | Centre for Sustainable Healthcare.

A Greener 'Hub' - A more sustainable vision for medical education within the undergraduate hub.

By: Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

See Clinical and Health Outcomes and Social Sustainability sections below

£623.39 (Actual)

538.16 kgCO2e (Actual)

Team Members:

- Cleone Pardoe – Clinical Teaching Fellow, Post-IMT2 Doctor,

- Alexander Strother – Clinical Teaching Fellow, Post-FY2 Doctor,

- Linh Mao – Undergraduate Medical Education Clerical Officer & Receptionist,

- Amanda Shotton – Undergraduate Medical Education Service Manager

Project Aims:

- Reduce the impact of our self-directed practice (SDP) rooms across the triple bottom line, by streamlining equipment packs for our 5 most popular skills: NGT, ABG, cannulation, venepuncture and catheter skills.

- Empower students to be conscious of the financial and environmental cost of items they use in the SDP and clinical environments.

- Save the Undergraduate department money, that can be better invested into improving the student experience and promoting sustainable healthcare.

Background:

Based at St James’s Hospital, the ‘Hub’ represents the heart of Undergraduate Medical Education at LTHT. We consist of a diverse education and administration team and are committed to being a place of teaching excellence to the roughly 200 MBChB and Physicians Associate students rotating through our department every month. Further, not only do we facilitate teaching sessions on countless topics, we deliver simulation training, run mock examinations and have two dedicated ‘self-directed practice’ (SDP) rooms, equipped with everything students need to hone their clinical skills independently.

As a Medical Education team, we believe we are uniquely placed to promote ‘greener’ healthcare systems by preparing future clinicians to deliver first-class care to an ever-more complex patient population. As individual clinicians, we will likely care for thousands of patients throughout our career. But as educators, we play a role in training hundreds of students every year, who will in turn care for hundreds of thousands of patients. We believe that by educating future clinicians at this early stage in their training on the importance of sustainable healthcare, we can support delivery of truly holistic care that both protects and promotes the health of current and future generations.

Approach:

Studying the system: A review of the booking system identified which skills were most popular in the past 12 months as well as then process students would go through to use the room. This process involved an online booking system where students detailed when and what skill/s they wished to practice. Upon arrival at the hub students were given equipment they needed in the form of a specific ‘pack’, according to a list that had been in use for many years. A baseline audit of storeroom inventory and SDP room use audit identified items that were

- Not required (unnecessary to the student experience nor reflective of real-life clinical practice)

- Required and potentially reusable

- Required and single use (needs to be replaced and purchased each time)

- Damaging to expensive equipment (e.g., alcohol-based cleaning solutions damaging to material of training arms, reducing their life span)

- Missing from the packs, which would be beneficial for student experience (e.g., gauze).

Engagement: Students were engaged to ensure a balance between sustainable changes and keeping an authentic and realistic experience for the students to practice their skills. A brief electronic questionnaire accessible via QR codes provided insight into why current students were using the SDP rooms, what an ‘ideal’ SDP was for students, and their thoughts on sustainable practice. This also supported us in developing our change ideas.

Changes implemented: We created new, sustainable ‘packs’, that could be collected by students when they arrived for their session. Metal trolleys were added to each SDP room, stacked with repurposed, labelled containersfor students to put their unused and potentially reusable equipment in when finished. Each label included the price of the relevant item, demonstrating how much money their simple actions could save, empowering students to take their learning into the clinical environment. The sustainable packs are remade at the end of each week with the reusable items students have placed in the trolley, with single use items (e.g., canula) added as needed. Each skill pack has a clear, illustrated document of what needs to be included to facilitate this process. A running total of CO2e savings with equivalent to miles driven in a car is shared on each room whiteboard and will be updated at the end of each month highlighting the environmental savings from their actions.

Measurement:

Financial: Price per unit was obtained from a comprehensive costing list from the Trust Supplies and Procurement team. We calculated savings by reviewing what we had saved through: a) removing unnecessary items; and b) reusing items that were previously thrown away. We added an additional cost to purchase cannulas, which were previously included as part of a larger pack (given free to the hub) that had contained several unnecessary items.

Environmental: CO2e were calculated for every piece of equipment based on the item cost or weight with the relevant emissions factor from the Carbon factors Greener NHS Team 2020-21. We used our audit to compare how many items were required pre and post introduction of our new sustainable packs.

Social: A questionnaire to collect both qualitative and quantitative data from our students ensured their voices were heard and at the heart of our initiative. This questionnaire sought to determine a number of important variables, including the students’ wider views on the importance of sustainable healthcare as discussed above. It could be completed quickly and easily by scanning one of QR codes found in each SDP room, which would direct students to our Google form. These QR codes will remain available to the students beyond the Green Ward; we are always open to ideas on how we can improve these spaces for their learning and the planet. Informal, qualitative data from the wider education team on how they have been inspired by the project and how they might change their practice as a result.

Results:

The balance for each ‘pack’ was calculated and used to predicted savings over 12 months, based upon the previous 12 months’ usage of the SDP room.

Environmental benefit: The total predicted savings amounted to 538.16 kgCO2e. This is the equivalent to 1,544.12 miles driven in an average car.

Financial benefit: The new packs will save our department £623.39 per year.

Clinical and health outcomes: The potential clinical impact is vast due to the huge number of students who come through our SDP rooms and already work in clinical environments on their placements. Our student feedback questionnaire identified 42.9% students had never previously considered the environmental impact of their clinical skills. When asked whether students had changed their practice to reduce waste, their responses were again encouraging:

“Yes - not using what is not necessary to practice examination”

“After this, I will be more mindful of how much equipment I take out of their packets on the ward”

Social sustainability: We were pleasantly surprised by how engaged students were in this process; the trolleys were overflowing with unused and potentially reusable equipment, and everything was in its correct tray. In response to asking if there was anything more we could do in addition to our current, thoughtful changes, the students responded positively:

“Not based on the environmentally friendly packs given today. They were sufficient for practicing the technique”

Without the engagement of our students in this culture change, the remaking of the kits at the end of each week would be time consuming to our staff. Fortunately, we found that both staff and students have very willingly engaged, and there have been no issues in terms of compliance for students to return equipment as requested, and no complaints from staff into the time taken to remake packs at the end of the week.

Our project has also sparked enthusiasm and conversation for sustainable medical education not only within our own team, but across the student cohort, management and Postgraduate teams. Amanda, Undergraduate Medical Education Service Manager, attended regular meetings and updated key stakeholders throughout the project which was vital to this engagement. Please see below some reflections from the Undergraduate team:

Ellie (CTF): “This project has changed my clinical practice - I now ensure I only take the equipment I need for each clinical skill”

Jordan (Medical Education Administrative Coordinator): “The whole project has been eye-opening. It has been great to see how much the students have got on board with the initiative”

Steps taken to ensure lasting change and conclusion:

We believe the ongoing success of this project is possible due to the positive engagement and dedication of staff and students alike. Through our discussions with staff, clinicians and students, one thing is clear: people genuinely care about sustainability, especially students. We believe we have empowered students to be more mindful of the financial and environmental impact of their clinical practice. Both ‘mindful’ and ‘conscious’ were words used by our students in their questionnaire responses. This will ensure not only that our SDP room changes continue, but that students will move on to clinical work with both competence in their skills and awareness of environmental impact of their care.

We have further ideas to further enhance our sustainable teaching including going paperless via use of QR codes to share information, a digital educator platform, and use of iPads which have recently been funded (saving 26,280 sheets of paper and additional 113.72KgC02e per year). We are also working on delivering an interactive workshop on sustainable healthcare to newly graduated junior doctors, on the principles of sustainable care and how we can integrate these with practice.

Our project has sparked enthusiasm and conversation for sustainable medical education across the student cohort, management and Postgraduate teams. We are motivated to ultimately extend this platform to those involved in medical education across the region and are equally inspired by our interactions with students from the Leeds Healthcare Students for Climate Action (HESCA) and Planetary Health Report Card; two student-led initiatives which seek to inspire medical institutions to adopt and promote sustainable healthcare practices in the UK and worldwide.

Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust - St James’s Hospital

Project developed as part of the 2022 Leeds Green Ward Competition. Full impact report available at Green Ward Competition | Centre for Sustainable Healthcare.

Reduce Disposables on Abbey, Otter, and Dart Wards – Housekeeping Team

By: Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust

£1274

82kgCO2e (Estimated)

The housekeeping team carried out 2 projects on Otter ward and have since spread changes to Abbey and Dart wards.

Project 1:

Goal: To replace plastic teaspoons with reusable metal spoons.

Background: On the 24-bedded ward around 100 plastic spoons are used each day for three meals for patients & hot drinks for patients and staff. The housekeeping team suggested reducing waste by introducing metal spoons.

Approach: Buy metal teaspoons and stop buying plastic teaspoons.

Results: The cost of water and electricity used to run the dishwasher, the carbon conversion factors for the materials used to make the spoons and the cost of the waste recycling, together with the weight of the two types of teaspoons was used to calculate environmental and cost benefits of this project.

Cost savings: Over 1 year the cost savings would be £245 for a single ward and has the potential to save £7338 if this change was made successfully on 30 wards. These figures include costs of dishwasher use (energy and water) and a waste of 10% of spoons due to damage. If spoons were retained in the ward, then savings would increase year on year.

Environmental savings: 42 kgCO2e were saved by this change.

Social savings: demonstrating good stewardship of resources and including environmental impact into decisionmaking about housekeeping in a healthcare setting.

Next steps: This project has been selected for the concept to be spread to other areas of the hospital.

Project 2:

Goal: to reduce plastics waste from serving orange juice on the ward.

Background: individual portions of orange juice are served in small plastic pots. These are handed out to, on average, 20 patients at lunchtime and at the evening meal.

Approach: instead of buying individual portions of orange juice the ward bought hard plastic tumblers and 1 litre cartons of orange juice. The cost of water and electricity used to run the dishwasher, the carbon conversion factors for the materials used to make the different packaging and the cost of the waste recycling, together with the weight of the two types of packaging was used to calculate environmental and cost benefits of this project.

Otter, Abbey and Dart wards - RD&E

This project was part of the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare's Green Ward competition

The Centre for Sustainable Healthcare runs the Green Ward Competition as a clinical engagement programme for NHS Trusts wishing to improve their environmental sustainability and reduce their carbon footprint.

Minimising Inappropriate Use of Dietary Supplements - Nutrition and Dietetics

By: Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust

Goal: The aims of the project were to reduce the inappropriate use of oral nutritional supplements (ONS)

Background: ONS are easily accessible to ward staff and there has been very little monitoring or control over their distribution. The dieticians postulated that ONS were often given to patients, without a review by a dietician. This was confirmed by an audit in December 2017 that showed a discrepancy between the number of dietician prescriptions for ONS per week and the number ordered by the catering department.

Inappropriate use of ONS has the potential to have a negative impact on patient health, for example if sugarcontaining ONS are given to diabetic patients (ONS were given out by catering staff who do not have training on diabetes) or if patients are not assessed adequately and given professional advice on diet and nutrition (for example drinking milk rather than using ONS in patients less ‘at risk’ of malnutrition).

Furthermore, if patients are discharged to the community with inappropriately dispensed ONS this has the potential to incur large costs for GPs as ONS are cheap for hospitals to provide (1p each) but much more expensive to provide in the community. The prescriptions are sometimes, but not always, reviewed in the community. Where prescriptions are not reviewed unused ONS may accumulate in patient’s homes and go to waste.

Approach: establish a more effective management system for the supply and storage of ONS at the RD&E Wonford Hospital at ward level

Progress:

Designing a system:

• the team were aiming to devise a simple, reliable and uniform system to supply ONS to all wards, regulating distribution but also allowing for large volumes of ONS to be available for patients being discharged with little advanced notice.

• part of streamlining the system involved reducing the number of different ONS supplied by wards. It has been difficult to gain consensus on which reduced range of ONS to use in different locations and this work continues.

• When piloting the system, the Datix system was used to log any problems encountered.

• Prior to the launch information was disseminated about the new system by arranging meetings open to clinical stakeholders (e.g. matrons, registered nurses, HCA’s, ward housekeepers, dietitians, logistics, catering). Meetings were poorly attended and some email addresses were out of date.

Launching the system: The ‘Top Up’ ordering system for ONS was launched in September 2018. Under the new system:

• all ONS ordered can be tracked and monitored using bar codes.

• The dieticians complete prescription forms for the ward housekeepers so that the housekeepers know which patients are prescribed ONS, which ONS are due and how frequently they should be given.

• There is also a section on the prescription form to help the ward housekeeper manage ward stock levels.

• The forms will also be used for monitoring. They will be returned monthly to the dietetics manager who repeat the audit carried out in December 2017 to see if the new system and communications with different teams has reduced the number of ONS being supplied to patients without dietetics advice.

Results: The re-audit is yet to take place, so results are awaited. The team have been learning about managing change including running a consultation process, decision-making in a large, diverse organisation and that disseminating information about change in an organisation is challenging and requires a multi-faced communication strategy.

Savings: In the long term it is hoped that the ‘Top-Up’ system will be embedded and that most ONS will be prescribed by dieticians. It is expected that this regulated distribution will have the down-stream effect that fewer patients will be discharged on inappropriately dispensed ONS, reducing the cost to NHS North, Eastern and Western Devon Clinical Commissioning Group and reduce the waste of unused ONS.

The Centre for Sustainable Healthcare runs the Green Ward Competition as a clinical engagement programme for NHS Trusts wishing to improve their environmental sustainability and reduce their carbon footprint.

Reducing Unnecessary Cannulation – Emergency Department

By: Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust

70% reduction in unnecessary cannulation

£ 27,830

8,400 kgCO2e

Goal: To reduce unnecessary cannulation in the emergency department (ED).

Background: before the project was carried out, inserting a cannula for a patient arriving in the emergency department was considered ‘routine’ care. Once a cannula is inserted the policy was for all cannula to be fitted with a Bionector, for infection control purposes. However, staff noticed when reviewing patients that many cannulae were inserted and not used or were used inappropriately (e.g. intravenous fluids or drugs used when the patient was able to drink and take oral medications). It was suspected that practice of inserting a cannula ‘routinely’ led to significant waste in terms of clinician time, waste of equipment required for cannulation, inappropriate use of intravenous fluids and medicines and unnecessary discomfort for patients. It was also noted that, where cannulae were likely to be short term, such as in theatres or the resus section of ED then Bionectors were not mandated, but in the main ED it was still expected that patients should have Bionectors attached to cannulae even though cannulation is often only required short term in ED.

Approach: The ED team planned to carry out an audit to test the hypothesis that a significant number of cannulations were unnecessary. ED consultants raised awareness of the audit prior and during the audit at the thrice-daily team handovers and with a poster campaign (posters put up around the department and on equipment trolleys where the cannulainsertion kit was kept). For 1 week doctors and nurses inserting cannulae recorded information on the patient’s main clinical problem on admission, the intended indication for insertion, number of attempts at insertion (i.e. number of cannulae used), whether the cannula was used in ED and what the cannula was used for. The 6 proforma for recording data was handed out at handover and was available on equipment trolleys. A collection tray for completed proformas was placed in ED. After the initial audit the results were presented. Informal (at handover) and formal (presentation) education was carried out on correct use of cannulae including raising awareness of a revised policy for ED, agreed with the infection control team, that if a cannula is likely only to be required short term then a Bionector did not need to be attached.

After a round of education the consultants stopped mentioning the changes and the audit was then repeated 1 month later, again over 1 week, to see if the project and education had been effective and if any changes had been embedded.

Emergency Department, RD&E

Staff noticed that cannulae and bionectors were being inserted or used inappropriately in the ED

The Centre for Sustainable Healthcare runs the Green Ward Competition as a clinical engagement programme for NHS Trusts wishing to improve their environmental sustainability and reduce their carbon footprint.

The plan was deemed to be successful enough to be rolled out more widely.

Suggestions for future iterations of the project:

Other data that could be collected are:

• whether cannulae were used to take blood (if a cannula was not used then the use of usual blood-taking kit should be taken into account in calculations).

• time taken for cannulation, including time taken to gather equipment, wash hands etc (to generate average time saved).

• Number of patients admitted to ED during the time of the audit.

• Patient narratives on the experience of cannulation.

Medicine Waste Reduction - Ash Ward

By: Ashford & St Peter’s Hospital NHS Trust

£2,791

432kg CO2e

Goal: The aims of the project were to reduce wasted medicine and save staff time on medicine orders.

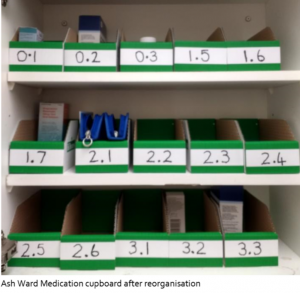

Background: The Team Leader identified that Ash Ward was wasting significant amounts of medicine and staff time on medicine orders. They decided to tackle the issue my addressing medicine order procedures and auditing medicine wastage.

Approach:

-

The medicine cupboard was redesigned to help ease storage procedures and patient own medication.

-

Montelukast was set a TTO prelabelled pack, meaning that patients did not have to return to the ward to

collect it. This cut down on pharmacy time and saved time for patients,

-

Antibiotic was kept in the fridge and stored for all patients, reducing antibiotic wastage.

-

Changes were communicated to all staff on the ward.

Savings:

Medicine waste data was collected at baseline and again after the changes. Before changes, 92 medicine orders, not including inhalers, were wasted over six weeks. After the change, this number dropped to 25 over six weeks. The savings project across a year equate to 558 medication orders. Assuming a cost £5 per average medication order, this would create yearly savings of around £2,791. Using the SDU pharmaceuticals carbon conversion factor, this amounts to 432 kgCO2e. Carbon and cost savings do not take into account waste disposal as the information was not available at the time of writing. Unfortunately, exact time saving data is not yet available, however these would significantly add to savings and have been qualitatively noticed on the ward in terms of staff satisfaction. The total yearly savings for this project could be around £2,791 and 432 kgCO2e.

The Centre for Sustainable Healthcare runs the Green Ward Competition as a clinical engagement programme for NHS Trusts wishing to improve their environmental sustainability and reduce their carbon footprint.

Discharge Checklist Planning - May Ward

By: Ashford & St Peter’s Hospital NHS Trust

£18,750 (Estimated)

4,757 kgCO2e (Estimated)

Goal: To reduce bed-blocking by training Band 5 nurses to conduct discharge checklists.

Background: The team found that patients who were ready to be discharged were taking up extra bed days in the ward due to senior nurses not having enough time to complete discharge paperwork. The team realised that by training band 5 nurses to do the same paperwork they would be able to help patients spend more quality time out of the ward and save bed days on the ward.

Approach: Although there was not enough time for the project to be run, the approach suggested was to include fast-track checklist training as part of zero-three month or six-month competency reviews.

Savings: It was estimated that this change could save 2.5 bed days per week. Assuming a cost of £150 per bed day, the yearly savings would amount to £18,750 and 4,757 kgCO2e.

May Ward

The Centre for Sustainable Healthcare runs the Green Ward Competition as a clinical engagement programme for NHS Trusts wishing to improve their environmental sustainability and reduce their carbon footprint.